Price Escalation and Price Adjustment Clauses in APAC

by Mark Alexander Grimes, Legal Consultant

Introduction

As the cost of materials, transportation and labour rise globally, construction projects are feeling the bite of evaporating margins, constrained cashflow, and extended lead times. Moving into a post-COVID operational environment, after a long (and continuing) period of reconciliation regarding COVID costs and delays, price escalation is becoming an urgent issue for global construction.

On top of COVID-driven inflation and delays, the commercial fallout of the conflict in Ukraine forced global supply chains and financing arrangements to adapt almost overnight, with an immediate impact on price-influencing fundamentals such as energy, iron/steel and other base metals. Unnervingly, a potentially similar economic shock could evolve from the increasingly tense international relations between China and Taiwan.

In this context, contractors and subcontractors are not only looking for ways to manage cost increases under existing contracts, but also becoming aware that if their future contracts do not provide for the risk of price escalation in the coming years, it could lead to further problems.

In this article, the latest in a series of regional articles by Systech, the overarching principles of contract price escalation are examined with reference to key forms in the APAC region.

What is ‘price escalation’?

Price escalation is sometimes known as ‘cost escalation’ or ‘material price escalation’. It refers to the sensitivity of construction contracts to the prices of materials and labour. In any fixed-price contract, the impact of rising costs in the supply chain will have a direct consequential impact on a contractor’s margin and cashflow. Under variable-price contracts, these are passed on to the Employer, with similar effects.

It is unusual to see variable pricing in major international projects, in part because such projects are typically dependent on financing from institutions. Often these institutions mandate the contractual arrangements on projects they finance but, even if not the case, project finance is generally based on detailed risk assessments that view open-ended, uncertain cost structures unfavourably.

New ‘target cost’ contracts are hybridising these contract models to an extent, essentially by providing a cost-reimbursable structure subject to a cap. Although these arrangements are enjoying some success in smaller domestic projects, it remains to be seen whether such arrangements will be used internationally.

As a result, all contract models are impacted by price escalation, but it is often contractors that bear the brunt.

...project finance is generally based on detailed risk assessments that view open-ended, uncertain cost structures unfavourably.

...all contract models are impacted by price escalation, but it is often contractors that bear the brunt.

Risk or requirement?

Price escalation is usually managed like any other risk, by being allocated under the contract. In the APAC region, as elsewhere, FIDIC is widely used for international contracts, in no small part due to its favoured status with major international development agencies such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, Asian Development Bank (ADB) and Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). AIA and ENAA[1] forms are also commonly used, while there are a wide variety of local standard form contracts.

The FIDIC and ENAA-influenced Standard Bidding Documents published by the World Bank, ADB and JICA all contain model price escalation clauses or appendices, illustrating the ubiquity of these clauses on major projects. However, whether these clauses are actually required to be included is variable. For example, World Bank and ADB Procurement Guidelines require price adjustment clauses in contracts longer than 18 months[2], whereas JICA Procurement Guidelines only ‘generally recommend’ such clauses for contracts over 18 months[3]. Therefore, contractors may not be in a position to negotiate the inclusion of a price escalation clause, particularly on shorter projects.

Local law is also a relevant consideration. Several APAC jurisdictions have laws impacting price escalation, with varying degrees of force, application and specificity. It is beyond the scope of this article to explore in depth, but at least a few Asian countries have laws that will require price escalation in construction contracts, while several have mandatory guidelines to be followed if price escalation is implemented. Some states limit their laws to contracts for public works, but others do not. This highlights that local law should always be considered in discussions of price escalation, including during tender, as the local law may override the contract provisions and, therefore, affect core tendering assumptions.

...contractors may not be in a position to negotiate the inclusion of a price escalation clause

...local law should always be considered in discussions of price escalation, including during tender, as the local law may override the contract provisions and, therefore, affect core tendering assumptions.

General principles

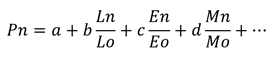

Price escalation clauses can seem intimidating, particularly with explanatory notes making reference to multiple coefficients (constants) and variables. For example, the World Bank’s 2021 Standard Bidding Documents[4] provide the formula:

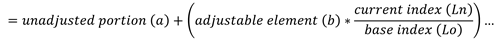

Despite appearing complex, the fundamentals of this formula, and most price adjustment clauses, can be explained as below:

The n in the above formula refers to a defined period. This is usually the relevant payment period and so will typically be the month of the payment application. The o refers to the base date. Therefore, it applies the difference between the base index and the current index to the adjustable price element, bringing the contract price up in line with the change in the index (or down, if de-escalation is permitted).

By referring to externally defined indices, there is no direct relationship to the actual costs incurred. In this sense, price escalation clauses are similar to clauses providing for interest at a defined rate: the purpose is not to be 100% accurate but only to provide a workable methodology that will broadly address the risk.

The mathematics involved are, therefore, relatively straightforward but the output of any formula is naturally dependent on the inputs which, although mathematical, are contractually defined. Consequently, both contractual and commercial review are essential.

What needs to be considered?

Careful attention should be given to define key variables, such as:

- The base date and/or start date

- Triggers for applying the clause

- Any caps on price increases

- Any non-adjustable portion

- Cost elements and weightings

- The relevant reference indices

- Whether different formulae are required for different costs

- Currency variables, if needed

- Any provisions for price de-escalation

As highlighted by some of the items above, the price adjustment clause can directly define the commercial success of the project for the contractor in an inflationary environment. As a prime example, triggers for price adjustment often require a certain degree of increase before the clause is engaged, while a cap may prevent any cost above a certain degree of increase being passed on. This effectively creates a window of defined margin on certain core costs, and allocates an open-ended risk above the cap.

Similarly, the non-adjustable portion is supposed to be a reflection of non-adjusting project overheads. Over a long-term contract, mis-estimation of this portion could lead to significant under-recovery.

Failing to properly consider key variables of the price adjustment formula can create disadvantageous commercial restraints on the contractor. Proper expertise should be employed in considering the price escalation clause, in line with other tendering assumptions. Modelling the potential impact of price increases over time may also be appropriate.

Renewable energy projects, for example, are particularly vulnerable to supply constraints in certain metals, with demand for those metals rapidly increasing as renewable energy targets come into view between 2030 and 2050. Modelling forecasted supply and inflation scenarios, and impacting the contract price via the draft price escalation clause, could prevent unnecessary surprises.

Proper expertise should be employed in considering the price escalation clause...

Modelling forecasted supply and inflation scenarios, and impacting the contract price via the draft price escalation clause, could prevent unnecessary surprises.

Conclusion

In the current macroeconomic environment, contractors are increasingly concerned about how to handle recent cost increases, which are unprecedented in the modern era. For contracts without a price escalation clause, a detailed contract review may provide avenues to recover certain costs under other headings such as change of law, force majeure, or the variation procedures. Local law may also allow recovery, depending on the jurisdiction.

In severe circumstances, commercial negotiation may become a necessity if the contractor is in risk of default, or if there are other risks to the project. Negotiated arrangements seen in practice include new financing, allowing some of the contractor’s proven costs to be deducted from liquidated delay damages, or new lump-sum contracts for work packages which are then removed from the main contract. All of these options are fraught with legal and commercial dangers and can bring further contentious issues if not handled carefully.

With a view to the future, including price escalation clauses in contracts may seem disadvantageous to employers, as they are accepting the risk of increasing costs. However, price escalation clauses allow contractors to bid more accurately and competitively, resulting in lower bid prices for the employer. It also opens the door to price de-escalation, which would favour the employer if deflationary trends prevail during the project.

Ultimately the most immediate benefit is that the project will not be endangered by contractor defaults, or contractor delays related to procurement and delivery issues arising from cost increases. In this regard, it should be borne in mind that the contractor’s delay is usually subject to liquidated delay damages, whereas the employer’s delay liability to other contractors is usually, at least theoretically, unlimited.

Although it may seem like a risk for employers to accept price escalation clauses, the current and continuing uncertainty in global supply chains may cause havoc on future projects if not appropriately provided for in the contract. In this respect, the certainty provided by price escalation clauses has significant value in itself.

For contracts without a price escalation clause, a detailed contract review may provide avenues to recover certain costs...

...price escalation clauses allow contractors to bid more accurately and competitively, resulting in lower bid prices...

...the certainty provided by price escalation clauses has significant value in itself.

References

[1]American Institute of Architects and Engineering Advancement Association of Japan, respectively.

[2]The World Bank, ‘Procurement Regulations for IPF Borrowers’, 4th Ed., November 2020; Asian Development Bank, ‘Procurement Guidelines’, April 2015

[3]Japan International Cooperation Agency, ‘Handbook for Procurement Under Japanese ODA Loans (English)’, April 2012.

[4]The World Bank, ’Standard Bidding Documents; Procurement of Works’, January 2021.